Introduction Part 1

You can access the slides for this lecture here.

Chip Multiprocessors

Below is an abstract (and over simplified) model of how architecture courses focusing on single core CPUs see a processor:

In the core of the processor we have an arithmetic logic unit (ALU) that performs the computations. We also have a set of registers that can hold the instructions' operands, as well as some additional control logic. There is also an on-chip cache holding recently accessed data and instructions. The processor fetches data and instruction from the main memory off chip.

In a chip multiprocessor, also called multicore processor, you have several instances of the core of the processor on a single chip:

In this example we have a dual-core. Each core is a duplicate of most of we will find in a single core CPU: ALU, registers, caches, etc. While a single core processor can only execute one instruction at a time, a multicore can execute n instructions at the same time

An interesting question to ask is: why were these chip multiprocessors invented?

Here are some pictures of transistors:

From a very simplistic point of view we can see these as ON/OFF switches that sometimes let the current flow and sometimes not. They are the basic block with which we construct the logic gates that are making the modern integrated circuits used in processors. Broadly speaking, the computing power of a CPU is function of the number of transistors it integrates.

if we consider the first processor commercialised, in 1971, it had in the order of thousands of transistors:

A few years later processors were made of tens of thousands of transistors. A few years later it was hundreds of thousands, and since the 2000s we are talking about millions of processors. Since that time processors also start to have multiple compute unites or cores. Before that they had only one.

Fast-forward closer to today we now have tens of billions of transistors in a single chip:

They also commonly integrate several compute units. The Intel i7 from 2011 has 6 cores. The Qualcomm Snapdragon chip is an embedded processor with 4 ARM64 cores. And a recent server processor with 64 cores. Why did processor started to have more and more cores? Why this increase in number of compute units (cores) per chip?

Core Count Increase

For over 40 years we have seen a continual increase in the power of processors. This has been driven primarily by improvements in silicon integrated circuit technology: circuits continue to integrate more and more transistors. Until the early 2000s, this translated into a direct increase of the single core CPU clock frequency, i.e. speed: transistors are smaller, we can pack more on a chip but they consume less, so they can be clocked faster. It was a good time to be a software programmer: if a program was too slow, just wait for the next generation of computers to get a speed boost.

But the basic circuit speed increase become limited. For power consumption and heat dissipation reasons, the clock frequency of CPUs has not seen any significant improvement since the mid 2000s. Other architectural approaches to increase single processor speed have also been exhausted.

Still, the amount of transistors that can be integrated in a single chip continued to increase. So, if the speed of a single processor cannot increase, and we can still put more transistor on a chip, the solution is to put more processors on a single chip, and try to have them work together somehow.

Say we want to create a dual-core processor. Will it be twice as fast as the single core version? It's not that simple and has several implications that we will cover in this course. First, in terms of hardware, what processor or what processor(s) to put on the multicore? How to connect them? How do they access memory? Second, from the software point of view, how can we program this multicore processor? Can we use the same programming paradigms and languages we used for single core CPUs? How can we express the parallelism that is inherent to chip multiprocessors?

The terms core and processor will be used interchangeably in the rest of this course

Moore's Law

This is not really a law, more an observation/prediction, made by an engineer named Gordon Moore. It states that the transistor count on integrated circuits doubles every 18 months.

The transistor count on a chip depends on two factors: the transistor size and the chip size. Consider the evolution of the feature size (basically transistor size) between the Intel 386 from 1985 and the Apple M1 Max from 2021:

| CPU | Feature (transistor) size | Die (chip) size | Transistors integrated |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intel 386 (1985) | 1.5 μm | 100 mm2 | 275,000 |

| Apple M1 Max (2021) | 5 nm | 420.2 mm2 | 57,000,000,000 |

As one can observe the size of a transistor saw a 300x decrease, while the size of the chip itself, only went down by 4x over the same period of time. We can conclude that the increase in transistors/chip is mostly due to transistor size reduction.

Smaller Used to Mean Faster, but not Anymore

Why do smaller transistor translate in faster circuits? From a high level point of view, due to their electric properties, smaller transistors have a faster switch delay. This means that they can be clocked with a higher frequency, making the overall circuit faster. This was the case in the good old days when clock frequency kept increasing, however that trend stopped in the early/mid 2000s: the transistors became so tightly packed together on the chip that power density and cooling became problematic: clocking them with too high of a frequency would basically melt the chip.

The End of Dennard Scaling and Single Core Performance Increase

Dennard Scaling was this law from a 1974 paper stating that, based on the electric properties of transistors, as they grew smaller and we packed more on the same chip, they consumed less power, so the power density stayed constant. At the time experts concluded that power consumption/heating would not be an issue as transistors became smaller and more tightly integrated.

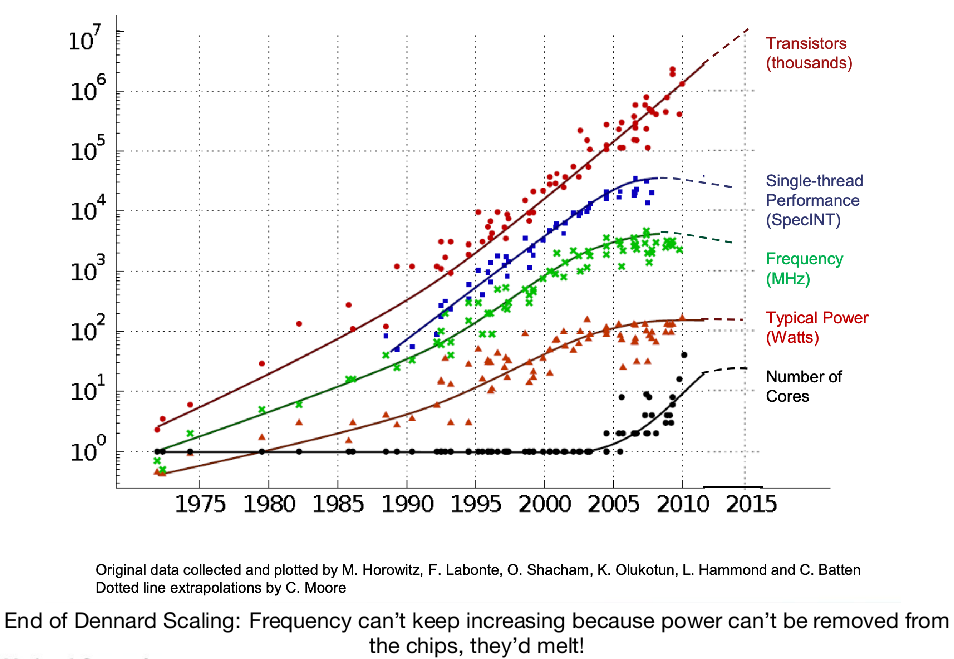

This law broke down in the mid-2000s, mostly due to the high current leakage coming with smaller transistor sizes. This is illustrated on this graph:

As one can see both the power and the frequency hit a plateau around that time, and single thread performance does to, proportionally. The number of transistors integrated keeps increasing, though.

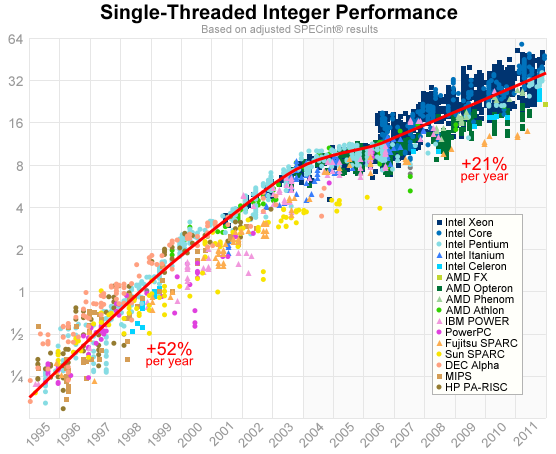

Here is another view on the issue, if you look at single threaded integer performance:

These numbers come from a standard benchmark named SPEC. As one can see the increase in performance has been more than divided by two. And if there is still some degree of increase, it does not come from frequency but from other improvements such as bigger caches or deeper / more parallel pipelines

Attempts at Increasing Single Core Performance

At that point we cannot increase the clock frequency, but we can still integrate more and more transistor in a chip. Is it possible to use these extra transistors to increase single core performance? It is indeed possible, although the solutions quickly showed limitations. Building several parallel pipelines was explored, to exploit Instruction Level Parallelism (ILP). However, ILP has diminished returns beyond ~4 pipelines. Another solution in to integrate bigger caches, but it becomes hard to get benefits past a certain size. In conclusion, efforts at increasing single core performance were quickly exhausted in the mid 2000s.

The "Solution": Multiple Cores

In the context previously described, an intuitive solution was to put multiple CPUs (cores) on a single integrated circuit (chip), named "multicore chip" or "chip multiprocessor", and to use these CPUs in parallel somehow to achieve higher performance. From the hardware point of view this represents a simpler to design vs. increasingly complex single core CPUs. But an important consideration is also that these processors cannot be programmed in the exact same way single core CPUs used to be programmed.

Multicore "Roadmap"

Below is an evolution (and projection) with time of the amount of cores per chip, as well as the feature size:

| Date | Number of cores | Feature size |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | ~2 | 65 nm |

| 2008 | ~4 | 45 nm |

| 2010 | ~8 | 33 nm |

| 2012 | ~16 | 23 nm |

| 2014 | ~32 | 16 nm |

| 2016 | ~64 | 12 nm |

| 2018 | ~128 | 8 nm |

| 2020 | ~256 | 6 nm |

| 2022 | ~512 | 4 nm |

| 2024 | ~1024 | 3 nm |

| 2026 | ~2048 | 2 nm |

| scale discontinuity? | ||

| 2028 | ~4096 | |

| 2030 | ~8192 | |

| 2032 | ~16384 |

As one can see we went from the first dual cores in the 2000s to tens and even hundreds of cores today. This has been achieved with the help of a significant reduction in feature size, however it is unclear if this trend can continue as it becomes harder and harder to construct smaller processors.