Lightweight Virtualisation

The slides for this chapter are available here.

Motivation

Imagine a company wishes to run a website, and do not want to leave a local machine up and running 24/7, so they decide to rent a virtual machine in the cloud They choose a cloud provider, say AWS, and select a Linux distribution to install on your VM, for example Ubuntu. So inside your VM the web server like Apache is installed, along with its library dependencies, things like perl, libssl, etc. When Apache runs, all this software makes use of a subset of the services offered by this massive guest kernel that is Linux. The setup we just described can be illustrated as follows:

On this illustration what really needs to run are the blue boxes: the web server, its dependencies, and the subset of kernel features it requires, that’s it. All the grey areas are installed and maybe even running but not needed. We call it software bloat, and it’s a bit of an issue.

Indeed, software bloat leads first to an increased attack surface: all the software installed in the Linux distribution, all the background programs running, and that you don’t really need represent potential targets for an attacker to take over and as a first step to attack your environment. Probabilistically, the more software you run, the higher the chances of a vulnerability to be present somewhere. Second, software bloat represents additional costs. The VM’s tenant is paying the cloud provider for disk, memory and CPU cycles used to store and run software they don’t even need. Third, for a fixed money budget software bloat also cause performance loss, because all this memory and CPU cycles are not used to run what really needs to run, which is you web server.

Definition

Lightweight virtualisation tackles this issue by providing the following properties, compared to traditional virtual machines:

- Lower memory footprint, in the order of kilobytes to a few megabytes of systems software overhead for each virtualised instance, compared to hundreds of megabytes or gigabytes of memory consumption for traditional VMs.

- Fast boot times in micro or milliseconds, compared to seconds or minutes for traditional VMs.

- Lower disk footprint, once again we are talking about a few kilobytes of megabytes.

Obviously these metrics regards the per-VM systems software, in particular the operating system. The part of the initialisation time and memory/disk footprint that relate to an application will stay the same if it runs in a lightweight or in a traditional VM.

Today there are 3 modern technologies that allow to achieve the aforementioned lightweightness objectives First, stripped down Linux VMs, called micro-VMs. These can be quite minimalist, but there are two technologies that take things one step further in terms of lightweightness: container and Unikernels. We’ll focus on containers and unikernels here, if you want to explore MicroVMs by yourself you can check out for example Firecracker.

Containers

Presentation

Containers are a process-based sandboxing technology, enforced by the operating system. A container management stack differs significantly from a system-level VM-based one:

Contrary to a traditional virtual machine, a container is a process or a group of processes for which the OS restricts the visibility on systems resources. This way the software running in the container is sandboxes, and it also feels it is running alone in the system, like in a virtual machine.

The resources which visibility upon can be reduced and changed for the container are the filesystem, the systems’ users, visible PIDs, IPCs, system clocks, among others. The OS can also control the allocation to the container of certain resources, including CPU scheduling cycles, memory available, disk and network bandwidth usable, among others.

Conceptually, by reducing or changing the visibility on resources, and limiting their allocation to a process or a group of processes, containers achieve the same isolation goals as a virtual machine, without the need for an hypervisor and a system-level VM. This is much lighter than using a traditional virtual machine. The boot time is that of spawning a process, a few microseconds, and the memory footprint is close to 0. Still containers are not perfect, and as we will see they suffer from significant security concerns.

Use Cases

Container are useful in most scenarios where virtualisation is beneficial. They are extensively used in software development, where they allow bringing up a homogeneous environment to develop, build, and test an application, for the entire development and testing team. Containers can also be used for deployment, as they represent a lightweight way to package an application with all of its dependencies. Docker is a prime example of container engine used extensively in software development:

Because they are so lightweight, container can replace traditional VMs for many aspects of cloud requiring very quick initialisation and execution of a particular task. Services such as Gmail or Facebook make extensive use of containers for such tasks. You may also have heard about AWS Lambda, which provides serverless computing services. With the serverless paradigm, the developer programs cloud machines with small stateless functions executed on demand when certain events happen, for example a user visits a web page. These functions generally run within containers.

Namespaces and Control Groups

Containers are enabled by two key technologies in Linux, restricting the view and usage of resources for processes: namespaces and control groups.

Namespaces restrict the view of the container on the following system resources:

- Filesystems and mount points: a container is generally given its own root filesystem from a based image, and it cannot access the host’s filesystem.

- Network stack: a container also has its own state of the network stack, including its own IP, with a virtual bridged and routed network.

- Processes: PIDs and IPCs: a container has also its own isolated set of PIDs, one for each process it runs. It cannot see or communicate with external processes.

- Host and domain name: a container can set the host name, which is the machine’s name, to something different than what the host sees. Same thing for the domain name.

- User IDs: usernames and IDs can also be different within the container, compared to what is on the host. In most scenario a user will simply take the identity of root within the container.

Control groups restrict a container’s usage/access/allocation of the following system resources:

- Memory: one can set the maximum amount of memory and swap a container can use.

- CPU: the CPU usage of a container can be rate-limited, for example the container can be allocated 1.5 CPUs. What CPU (core) a container can run on can also be restricted, and so ca be the scheduler’s quotas for the container.

- Devices: a container can also be restricted to seeing only certain devices.

- Block and network I/Os: a container’s disk and network throughput can be rate-limited.

Containers vs. VMs

If we list the respective benefits of containers versus traditional virtual machines, we get the following:

| Containers | VMs |

|---|---|

| Low memory/disk usage | OS diversity |

| Fast Boot times | Kernel version |

| Per host density | Performance isolation |

| Nesting | Security |

Containers are very lightweight, meaning they have a low memory and disk usage and very fast boot times. Their lightweightness allows creating a very high number of container on a single machine, it’s not uncommon to run hundreds or even thousands of containers on a host. Nested virtualisation is also easy with containers, in other words it’s simple to create a container within a container. Regarding virtual machines, they are still useful when one wants to run an operating different from Linux – something that is difficult to do efficiently with containers because they rely on the namespaces and control groups technologies available only with Linux. Several studies have also shown that performance isolation is stronger with VMs than with container, meaning it’s more difficult for a malicious VM to steal resources by abusing them. Finally, the degree of isolation for the sandboxing enforced by virtual machines is considered as much stronger compared to containers.

Containers and Security

To understand why the isolation in VM environments is considered as stronger compared to containers, let’s consider both setups:

We have a container environment on the left, with several containers running on top of the OS kernel. An on the right a VM environment, with several VMs running on top of an hypervisor. If we place ourselves in the shoes of the cloud provider, and reason about what we trust and we do not trust in such a setup, we shall conclude that: the virtualisation layer is trusted, that is the OS for the container environment, and the hypervisor for the VM one. The instances of either containers or virtual machines are obviously untrusted, who knows who the tenants are and what they run in their VMs/containers.

As the provider of virtualised environments, the kind of attacks we are very concerned about is often the following:

One of the containers or VM is malicious, and tries to perform an escape attack, that is, to get access to the virtualisation layer’s memory, or to the memory allocated for other containers or VMs. As we have seen in the past, hardware enforced isolation mechanisms such as the page table or extended page tables will prevent direct access from the malicious entity to other VMs or containers. The real threat lies in the virtualisation layer, which can be invoked by the malicious VM or container. If this invocation can manage to trigger a bug in the virtualisation layer, the isolation may be broken and the attacker could access the virtualisation layer’s or other container/VMs’ memory.

It is quite important to determine how complex is this interface between what we trust and what we don’t trust in both cases. The reason for that is because how complex translates into how hard it is“ to secure this interface and make sure there are no bugs.

In the case of containers, that interface is unfortunately very complex: it is the system call interface, which is made of hundreds of system calls, some of them like ioctl presenting thousands of sub-functions.

There is no way we can guarantee that the implementation of all these system calls is bug-free.

In fact, automated vulnerability finding systems will regularly find bugs on that interface.

Conversely, the interface between a VM and the hypervisor managing it is much simpler: it is just a few traps.

In that context, the isolation between containers is not considered to be as strong as that between VMs because of the complexity of the interface between containers and the privileged layer, the OS kernel. To illustrate this point, note that many actors running containers in production will actually run containers within virtual machines, to benefits from their strong isolation These approaches try to reduce as much as possible the memory footprint and boot times of Linux VMs, creating what they call micro VMs, however this still negates most of the lightweightness benefits of containers. An example of such technology is Firecracker.

Unikernels

Presentation

We have seen that traditional VMs are heavyweight but secure, and that containers are lightweight but insecure. Can we get both the lightweightness benefits of container, combined with the security benefits of virtual machines, into a single virtualised solution? Unikernels is a relatively new operating system model that aims to answer that question.

Recall our motivational example from earlier, presenting the software bloat that occurs in many situations when using traditional VMs. Using unikernels we would address the problem as follows:

With a unikernel we compile an application’s code as well as all of its dependencies with a very small operating system layer into a static binary which merges the application and the operating system. This binary can be run as a kernel, in a virtual machine, on top of an hypervisor.

A unikernel instance is single purpose and it runs a single application. To run multiple applications, one needs to run multiple unikernel instances. A unikernel instance is also a single process virtual machine, and once again to run a multiprocess application it is generally needed to execute several unikernel instances. Still, several unikernel models can run on a multicores CPU and leverage parallelism/concurrency with threads. Finally, as already mentioned in a unikernel instance the VM runs a single binary, containing the application, its dependencies, and the kernel. All of this code runs within a single address space, and there is no user/kernel protection. This is because there is only one application running in a unikernel instance, and the isolation between applications is already enforced by running them as separate unikernel instances.

The unikernel model was originally proposed in this seminal paper in 2013:

Madhavapeddy et al., Unikernels: Library Operating Systems for the Cloud, ASPLOS’13

Benefits & Application Domains

With that model, unikernels present a series of benefits. First, it’s a form of lightweight virtualisation. Because a unikernel instance only run the code absolutely necessary for the application in question, and that the OS layer is so small, we get similar benefits as with containers in terms of low memory/disk footprint, and fast boot times. Second, because they run as virtual machines, unikernels are well isolated and considered a secure alternative to container in many scenarios. Third, the OS layer within a unikernel instance can be specialised towards the application it runs: specialised kernel subsystems can bring higher performance, or lower memory footprint/power consumption for a particular application scenario. Finally, because a unikernel operating system is so small and simple, it does not get in the way of application’s performance as much as larger OSes such as Linux. This translates into increased performance for certain applications. Another noteworthy point regarding performance is the system call latency: with unikernels, because there is no user/kernel isolation, system calls are simple function calls which make them much faster.

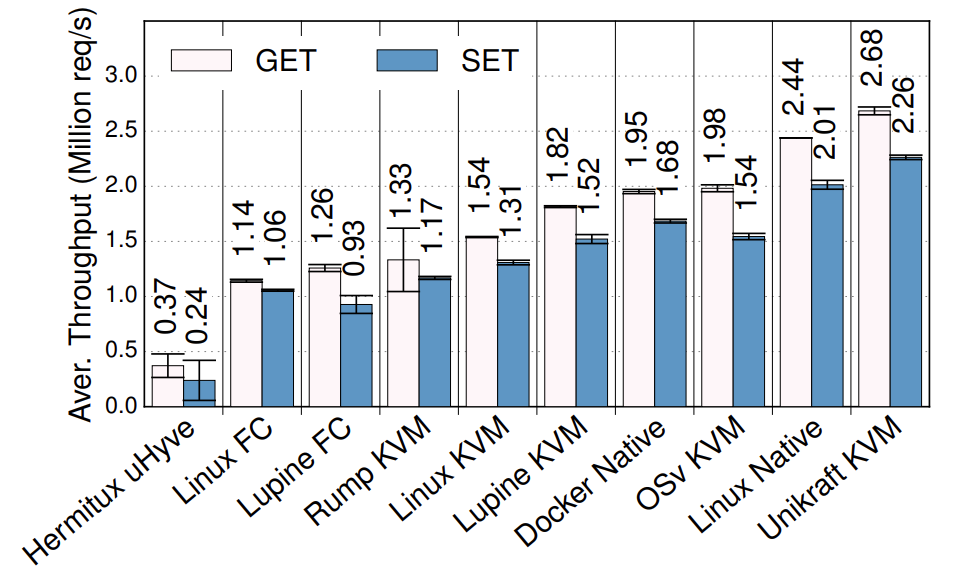

Just to illustrate the unikernel performance benefits that comes from their low latency system call, consider these results:

Redis throughput under various setups (higher is better)

This graph is taken from the Unikraft paper:

S. Kuenzer et al., Unikraft: Fast, Specialized Unikernels the Easy Way, EuroSys’21

The graph shows the throughput for Redis, which is a very popular key value store, in millions of requests per second. There are various setups on the X axis including different unikernels, as well as vanilla Linux. As you can see Unikraft is the fastest solution: even if it runs virtualised on top of Qemu/KVM, it is still a bit faster than Linux non-virtualised, and also much faster than Linux in a VM. Feel free to check out the paper for more performance evaluation.

Given these benefits unikernels have plenty of application domains. We motivated them with cloud environments such as server or microservice software. But they have also been explored in the domains of embedded virtualisation, edge computing and IoT. Network function virtualisation, high performance computing, and various security critical domains such as VM introspection, malware analysis, and secure desktop environments. Still an important point to note is that most unikernels are still at the stage of research prototype. This is different from containers which as you may know are a production-ready technology.

Unikernel Projects

A few examples of unikernel projects are listed below. Some of these are relatively unstable and poorly maintained academic research artefacts. The most mature project, the one that is the closest to production ready status, is Unikraft.

Unikernels can be classified based on the targeted language for supported applications:

- Pure memory safe languages (OCamL, Erlang, Haskell): MirageOS, LING, HalVM

- C/C++, semi-posix API: Unikraft, HermiTux, HermitCore, OSv, Rumprun, Lupine

- Rust/Go: Hermit, Clive

- More: https://unikernelalliance.org/projects/

Compatibility Aspects

Although they present desirable security and lightweightness benefits, unikernels also suffer from an important drawback which stems from their custom OS nature: a lack of compatibility with existing software and, to a lesser extent, hardware. On the hardware side, it is not possible for unikernel project to integrate the large amount of drivers supported by popular OSes such as Windows or Linux. Still, using the split driver model (frontend/backend) driver model we saw that is common in virtualised environments, a unikernel supporting popular paravirtualised (e.g. Virtio) I/O frontend drivers and running alongside e.g., Linux, will be compatible with numerous I/O devices. The real compatibility problem of unikernels rather lies on the software side.

One of the reasons unikernels are not particularly popular today, despite being around for more than a decade now, is that it is hard to run existing application on top of them. Most unikernels require access to an application’s source to compile it with the unikernel OS, so in scenario where the sources are not available for a given application (e.g., proprietary software), a unikernel cannot be created. Even when sources are available, as we’ve seen previously, most unikernel model support only one or a few programming languages, which limits compatibility.

Many applications will also require specific OS features available under e.g., Linux or Windows, but unsupported by most unikernel models. Porting is thus required: one can try to adapt an application to work on top of a unikernel model, or to enhance the unikernel model for it to provide the features required by the application. Often, porting involves doing a bit of both: it is time-consuming task which requires expertise in both the application to be ported, and the unikernel model to use, which discourages many prospective users.

Since that problem was identified, several research efforts attempted to enhance the compatibility issues of unikernels. The main idea is to require as little modifications/effort as possible to execute as a unikernel an application that already builds for and runs on top of a popular OS such as Linux. The compatibility can be achieved at various levels, from the weakest to the strongest:

- Source-level compatible unikernels (e.g., HermitCore, Rumprun): these require to recompile an application’s code with a custom C standard library and the unikernel kernel. It is a relatively weak form of compatibility, as the C standard library is not the only interface with the kernel in many applications. This approach also still requires recompilation and access to the sources.

- C standard library-level binary-compatible unikernel (e.g., OSv, Lupine): these interface an application at runtime with a custom C standard library, similarly to how shared libraries are loaded at runtime. These approaches may sometimes avoid recompilation, but are still limited to programs requesting OS services only through the C standard library.

- System call-level binary compatible unikernels (e.g., HermiTux, Unikraft): this is the strongest form of compatibility targeting the standard app/OS interface: the unikernel OS hooks into the system calls made by an application compiled for a popular OS (e.g., Linux) and emulates that OS behaviour. Such compatibility at the system call level allows running unmodified Linux application as unikernel without access to the sources/recompiling.

For more information on the topic of unikernels and application compatibility check out this paper:

Olivier et al., A Binary-Compatible Unikernel, VEE’19